- AI Engineering

- Posts

- GLM-4.7 vs MiniMax-M2.1: A Real Agentic Coding Test

GLM-4.7 vs MiniMax-M2.1: A Real Agentic Coding Test

... PLUS: AI agent for Jupyter notebooks

In today’s newsletter:

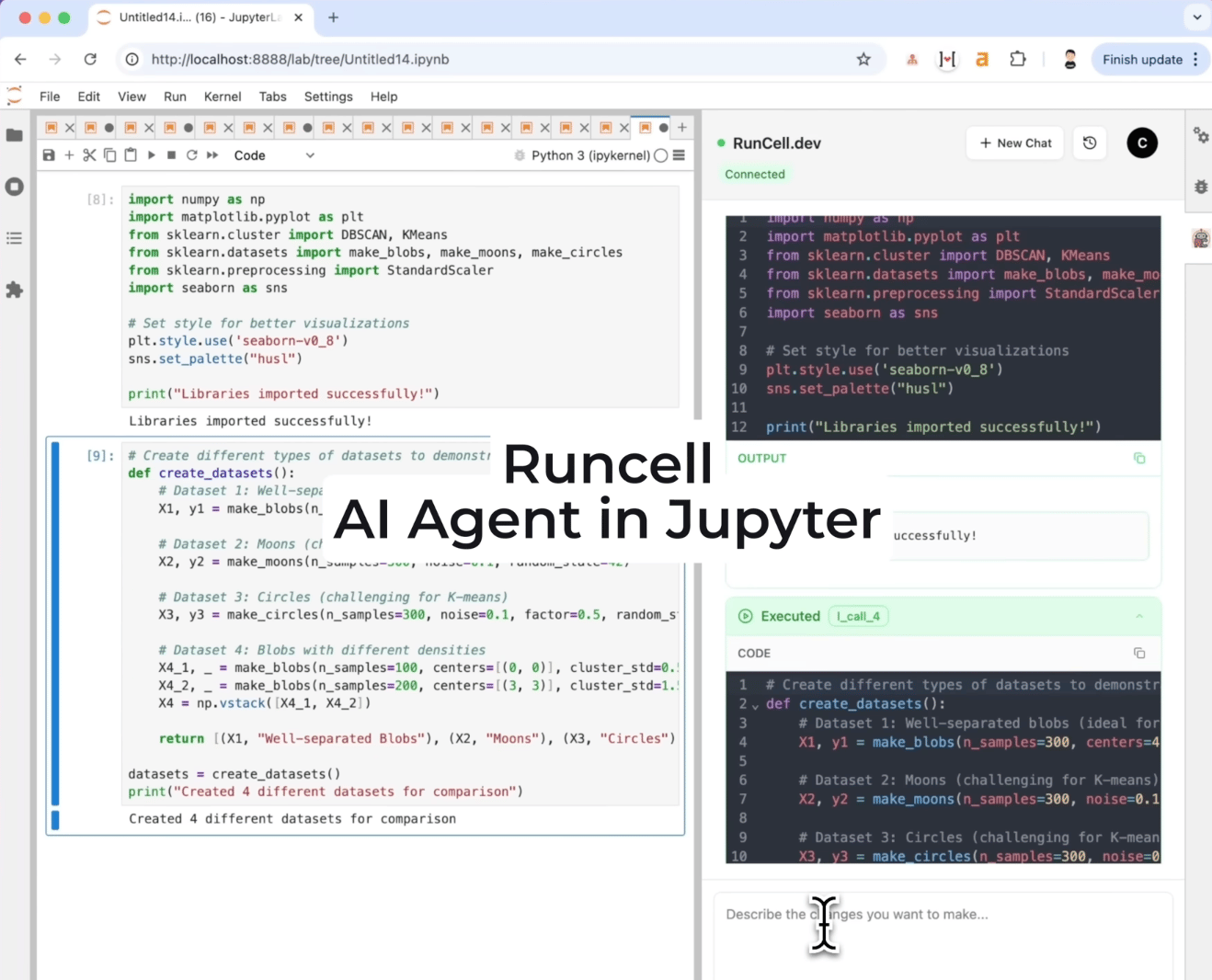

Runcell: AI Agent for Jupyter notebooks

GLM-4.7 vs MiniMax-M2.1: Open-Weight Models Building a 20-Feature CLI End-to-End

Reading time: 3 minutes.

Most AI coding assistants stop at text. They generate code, but you still copy it into cells, run it manually, debug errors, and repeat.

Runcell closes that loop.

It’s a JupyterLab extension that reads your notebook environment, including variables, DataFrames, and visualizations, writes Python code, executes cells, catches errors, and iterates until the task is complete.

This lets you work directly inside your existing notebooks while the agent handles writing, running, and debugging code.

Key features:

Reads and understands notebook context

Writes and executes Python code autonomously

Debugs errors and retries until tasks complete

Maintains context across cells

Works directly inside JupyterLab

Install with a single command pip install runcell.

A 30% discount is available using the code AIENGINEERING

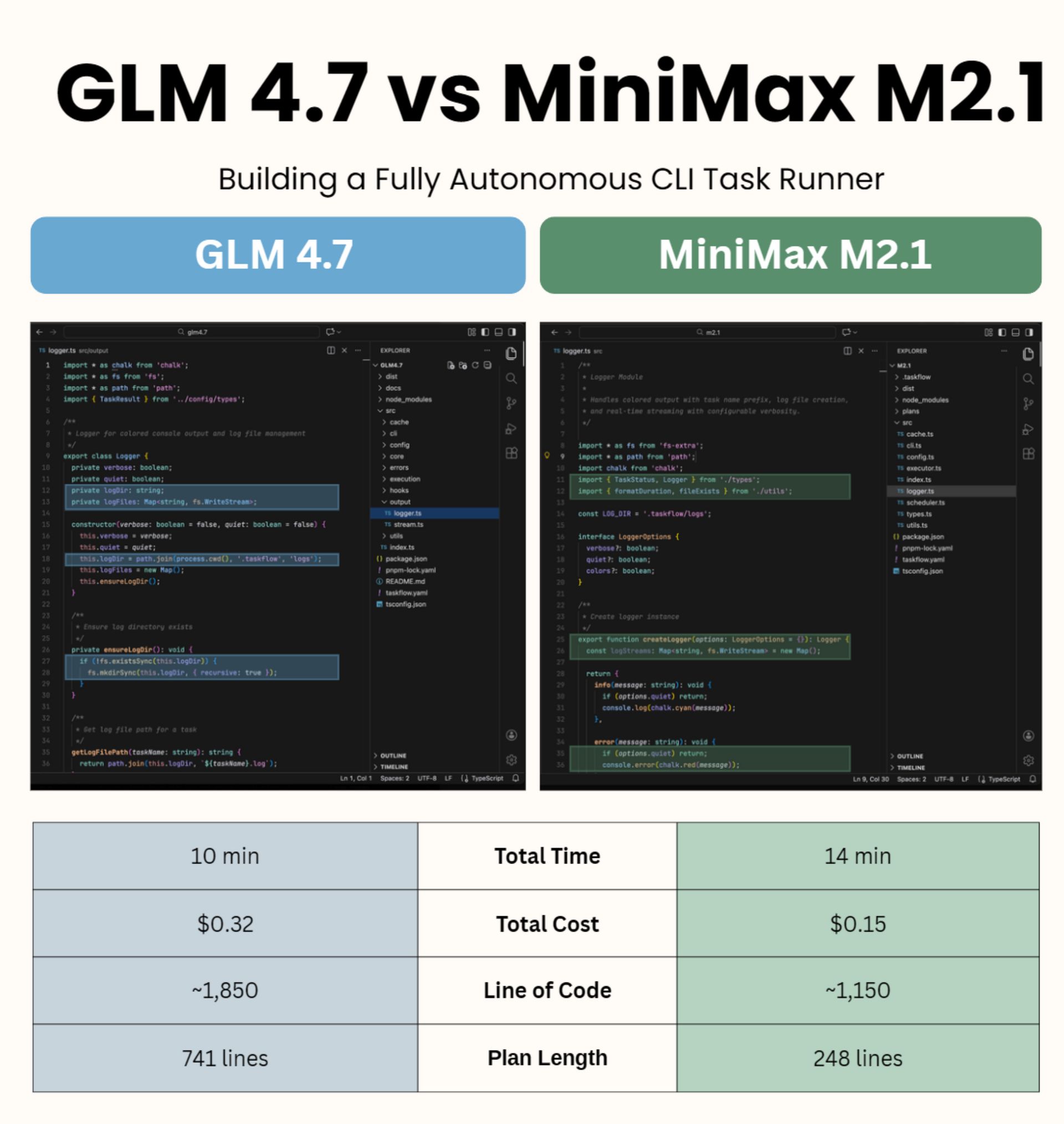

GLM 4.7 vs MiniMax M2.1

How capable are open-weight models when faced with real engineering work?

Kilo Code recently tested GLM 4.7 and MiniMax M2.1 by giving them a single, realistic task to build a fully-featured CLI task runner from scratch, end to end, with no human intervention.

Both models succeeded.

They planned the system, wrote the code, debugged issues, and validated the final output on their own, running continuously for 10 to 14 minutes. A year ago, seeing this level of autonomy outside frontier models would have been surprising.

So what exactly were they asked to build?

The task was to implement taskflow, a CLI tool that executes workflows defined in a YAML configuration file, similar to a lightweight GitHub Actions runner you can run locally.

That meant handling real engineering concerns, including:

Dependency graphs with cycle detection

Parallel execution with concurrency limits

Process spawning and signal handling

Input caching and retry logic

Configurable logging, hooks, and timeouts

This is the kind of tool a software engineer might spend one to two days implementing cleanly.

Two-phase evaluation: planning → execution

The test was split into two phases to evaluate true agentic behavior.

Phase 1: Architect Mode

Each model was given the full specification and asked to design the system before writing any code.

Phase 2: Code Mode

The models then implemented their own plans without further guidance.

No human steering. No mid-course corrections.

Phase 1: Planning styles diverge

The planning phase revealed a clear philosophical difference.

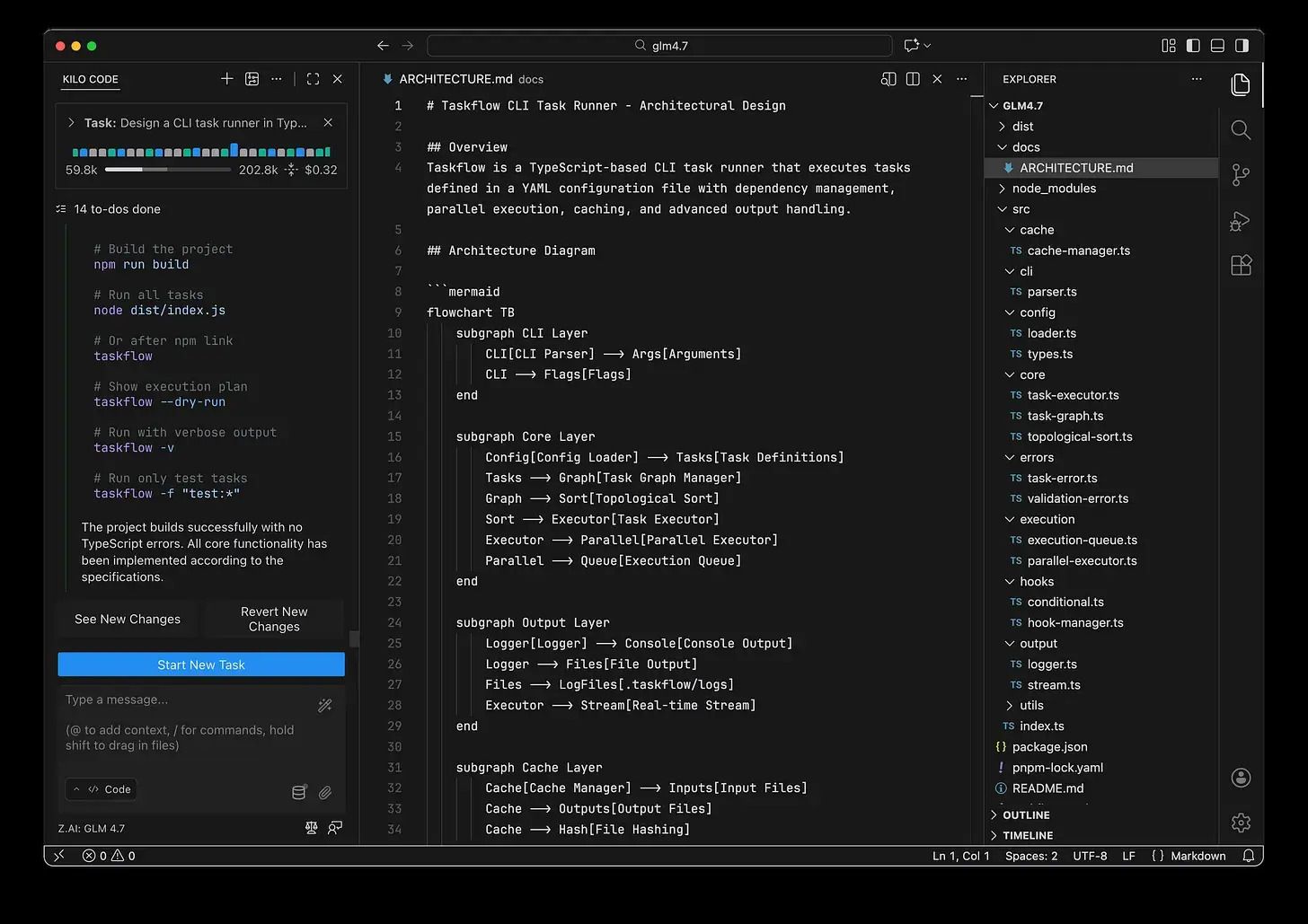

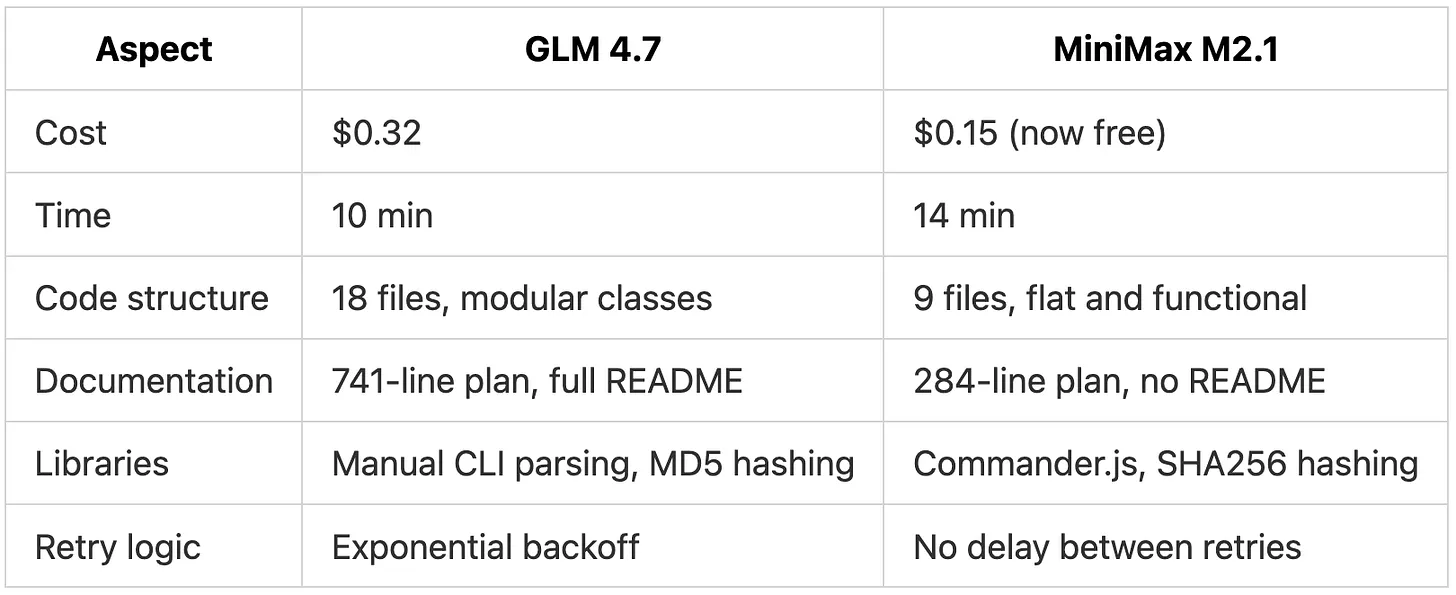

GLM 4.7 produced a 741-line architecture document, complete with Mermaid diagrams, detailed module boundaries, explicit algorithms (including Kahn’s algorithm for topological sorting), and a step-by-step implementation roadmap. It even included security and performance considerations.

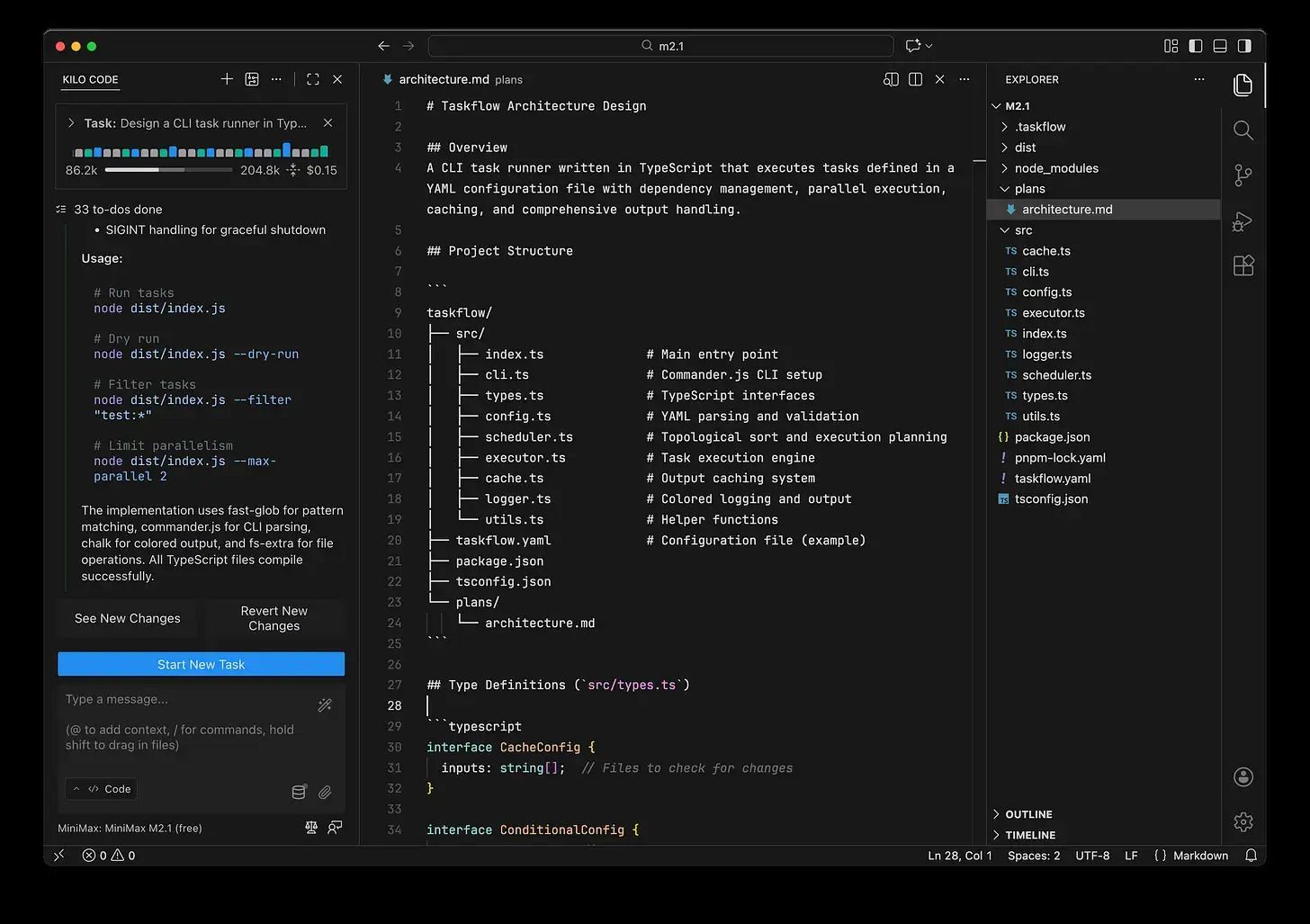

MiniMax M2.1 produced a much shorter 284-line plan. It covered all required concepts, but with far less narrative detail. The architecture was flatter, and the plan read more like a working specification than internal documentation.

Both plans were technically correct.

Phase 2: Both models deliver working code

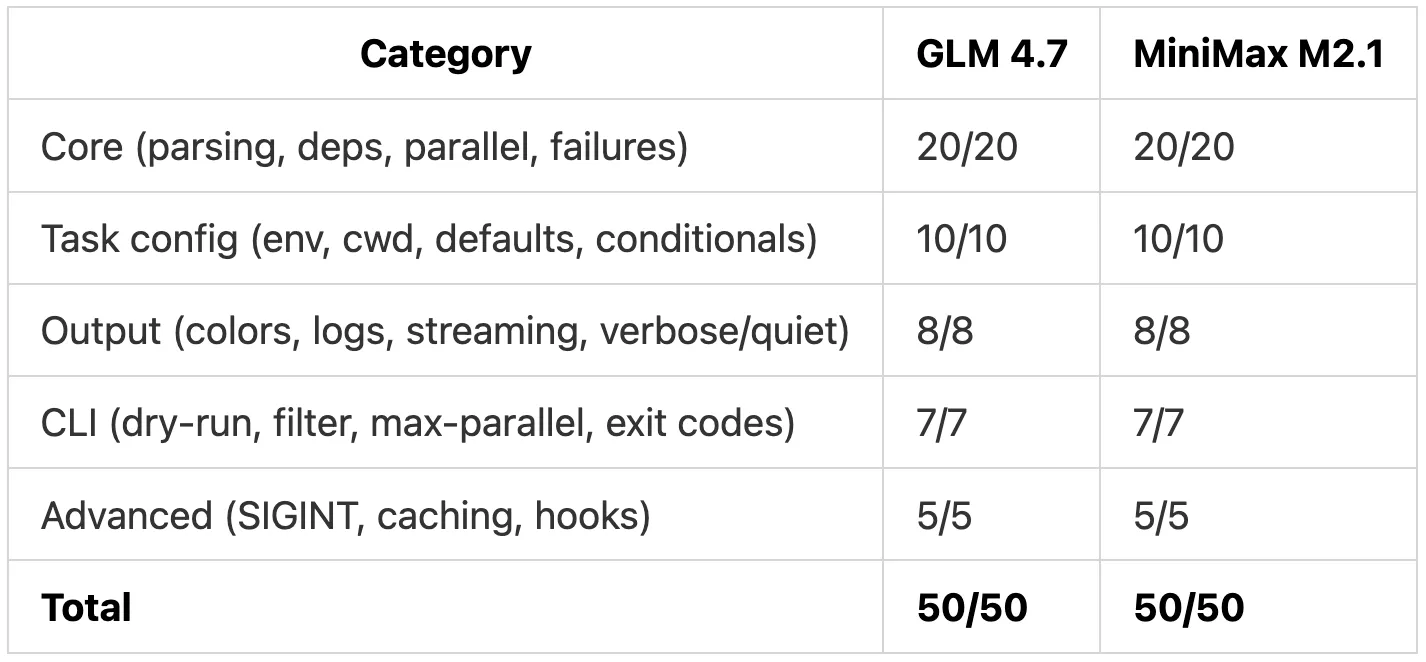

Despite their different planning styles, both models successfully implemented all 20 requirements.

The resulting CLI tools compiled, ran, and passed functional tests without major issues.

The differences showed up in how each model approached the implementation:

GLM 4.7 produced a highly modular codebase with 18 files, used exponential backoff for retries, and included a 363-line README

MiniMax M2.1 took a flatter approach with 9 files, retried immediately on failure, and shipped without documentation

A real agentic moment: self-debugging

The most interesting moment came during MiniMax M2.1’s execution.

While testing its own output, it noticed a CLI flag wasn’t being parsed correctly by Commander.js. Instead of failing or asking for help, the model wrote a small inline Node.js test, isolated the issue, fixed the parsing logic, and reran the tests successfully.

No human intervention.

This is what genuine agentic behavior looks like in practice.

Cost and tradeoffs

At the time of testing:

GLM 4.7 cost ~$0.30

MiniMax M2.1 cost ~$0.15

Both are dramatically cheaper than frontier models, which would cost several dollars for the same task.

The performance gap came entirely from documentation depth, not functional quality.

What this means for AI engineers

A year ago, autonomous coding like this was limited to expensive frontier models.

Today, open-weight models can:

Plan complex systems

Execute multi-file implementations

Debug their own failures

Validate outputs independently

The gap between “affordable” and “best” is shrinking fast.

If you care about cost efficiency, MiniMax M2.1 already gets you there.

If you value structured documentation and modularity, GLM 4.7 delivers more out of the box.

Either way, open-weight models are now serious engineering tools.

Kilo Code makes running these comparisons practical. With Parallel Mode, you can run the same task across multiple models at once and compare the results side by side, choosing between cost and quality without changing the workload.

That’s all for today. Thank you for reading today’s edition. See you in the next issue with more AI Engineering insights.

PS: We curate this AI Engineering content for free, and your support means everything. If you find value in what you read, consider sharing it with a friend or two.

Your feedback is valuable: If there’s a topic you’re stuck on or curious about, reply to this email. We’re building this for you, and your feedback helps shape what we send.

WORK WITH US

Looking to promote your company, product, or service to 160K+ AI developers? Get in touch today by replying to this email.